A new survey paper from Caltech and Stanford—“Large Language Model Reasoning Failures” by Peiyang Song, Pengrui Han, and Noah Goodman—systematically catalogues how and why large language models fail at reasoning. Not anecdotally. Not with vibes. With a comprehensive taxonomy covering hundreds of studies, organizing the failures into categories that make the patterns impossible to ignore.

Over the last several months, I’ve published over 50,000 words of documented results from experiments testing AI against creative writing—developmental editing, generation, evaluation, sensitivity reading, spatial modeling, prose quality, across multiple systems and hundreds of thousands of words of manuscript context. The conclusion I kept arriving at was that the limitations I was finding weren’t engineering problems waiting for better models. They were architectural. Fundamental to how these systems work.

The paper just organized that exact argument into a comprehensive taxonomy and systematic framework. And the mapping between their taxonomy and my experimental results is uncomfortably precise.

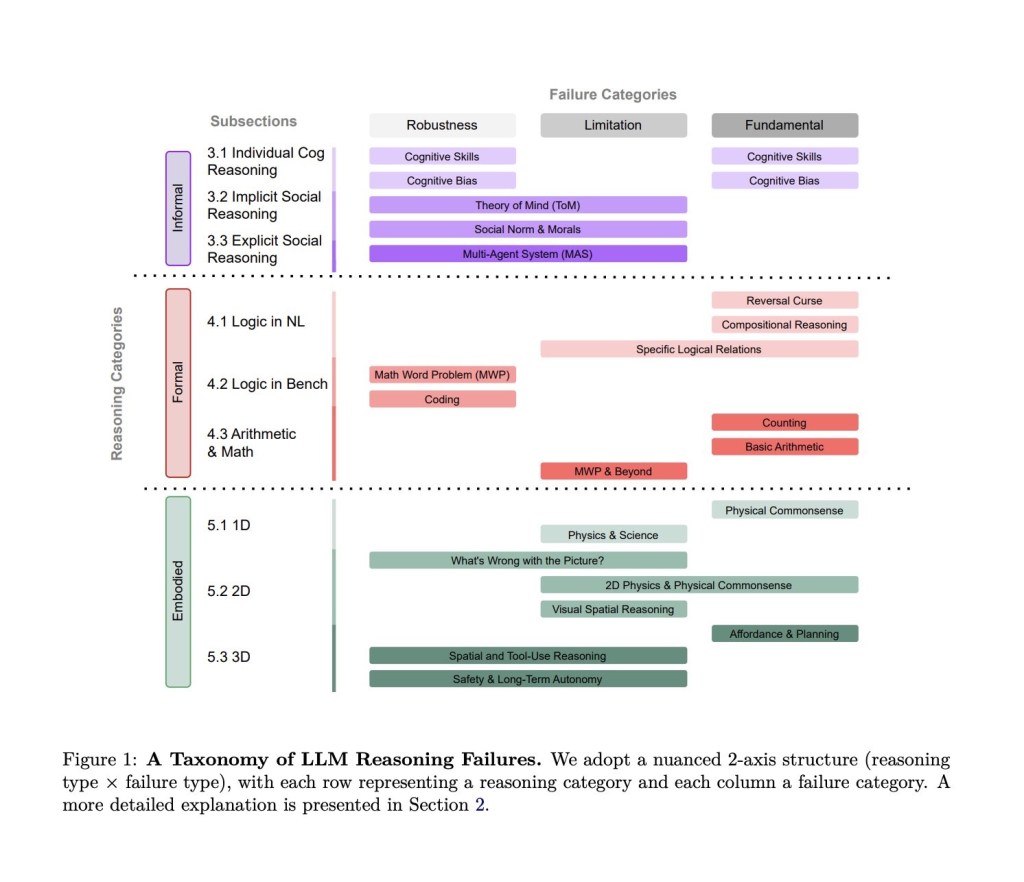

Song, Han, and Goodman classify LLM reasoning failures along two axes: the type of reasoning being attempted (informal, formal, or embodied) and the type of failure (fundamental architectural limitations, application-specific breakdowns, or robustness issues where minor input changes flip the output entirely). That second axis is where my experiments live.

Start with fundamental architectural failures—models generating output that looks coherent but collapses under logical pressure. The paper documents how LLMs shortcut, pattern-match, and hallucinate reasoning steps instead of executing consistent processes. I documented this across three AI systems evaluating the same manuscript. When I tested Grok, Claude Sonnet, and Claude Opus as developmental editors on my novel The Stygian Blades, each model generated confident, sophisticated-sounding feedback. Grok called my literary fantasy “pulp” and compared it to Fritz Leiber. Sonnet demanded I collapse my parallel plotlines into structural unity. Opus wanted more character agency from a protagonist whose reactivity is the entire point. My professional editor with fifteen years of experience didn’t mention any of these things—in fact he told me specifically not to rewrite anything in the book because everything was working; it just needed some extremely limited and targeted scaffolding added—none of which the models caught. Three AI systems, three different sets of wrong notes, all delivered with equal confidence, each one pattern-matching against different training data heuristics rather than understanding what the manuscript was actually doing.

The paper also identifies what it calls unfaithful reasoning: models that produce correct final answers while providing explanations that are logically wrong, incomplete, or fabricated. The authors argue this is worse than simply being wrong, because it trains users to trust explanations that don’t correspond to the actual decision process. I watched this happen in real time. When I asked Grok to improve my opening scene to a “solid 10/10,” it produced a rewrite that stripped character voice, replaced load-bearing subtext with exposition, and added a mysterious cloaked figure watching from the shadows. When I fed that “perfect” rewrite back to Grok in a fresh session, it rated it 7/10 — it couldn’t recognize its own supposedly perfect work. But it defended every change it made with craft terminology that sounded sophisticated and was completely wrong. The reasoning was unfaithful: the explanations existed to justify the output, not to describe how the output was produced.

Then there are robustness failures—the paper’s term for outputs that flip entirely based on minor changes in wording, ordering, or context. The reasoning wasn’t stable; it just happened to work for that particular phrasing. This is what I found when the same manuscript produced wildly different evaluations across models. But it’s also what the Purple Thread experiment revealed at a deeper level: Claude Sonnet consistently misidentified its own AI-generated prose as the human author’s work across multiple sessions, praising “sophisticated control” and “masterful understatement” while dismissing the actual human writing as “too raw.” The evaluation heuristics weren’t robust—they were artifacts of which patterns happened to fire for that input.

When Opus 4.5 ran the same test against Sonnet’s writing, it got the answer right seven out of seven times. Different model, dramatically different result. But when I ran the same experiment pitting Opus 4.6, arguably one of the most advanced and sophisticated LLMs on the planet, against its own generation rather than Sonnet’s, it failed—repeatedly picking its own prose as the human work, praising constructed symbolism as organic and dismissing authentic voice as craft weakness.

Opus could see through Sonnet’s writing. It couldn’t see through its own.

The recognition capability wasn’t general; it was contingent on the gap between the evaluator’s sophistication and the writing being evaluated. Close that gap and the heuristics collapse.

The category that connects most directly to my work is embodied reasoning, and it’s where I think the paper’s framework is most useful but also most incomplete.

The paper documents how LLMs systematically fail at physical commonsense, spatial reasoning, and basic physics because they have no grounded experience. Even in text-only settings, as soon as a task implicitly depends on real-world dynamics, failures become predictable and repeatable. I found exactly this when testing AI’s ability to draft action scenes. Claude wrote a house fifteen meters from a wall, then two paragraphs later placed it ten meters away. When I pointed out the error, Claude explained why in terms the Stanford paper would recognize: “I’m not working from a spatial model. I’m producing sentences that sound like action scene description. Each sentence is locally coherent, but I’m not maintaining world-state across them.” That’s a plain-language description of the paper’s embodied reasoning failure category. The system doesn’t have a world model. It has next-token prediction that breaks the moment a task requires maintaining state.

But the embodied reasoning gap extends beyond spatial modeling into something the paper’s framework captures without quite naming—something I’d call experiential reasoning. The ability to filter reality through consciousness shaped by lived experience. This is, I believe, the actual load-bearing distinction between what LLMs do and what writers do, and it’s the one that matters most for understanding why these systems fail at creative work specifically.

In my longest piece on this subject, I argued that pattern-matching against text about human experience is categorically different from having human experience, and that this distinction explains why AI can analyze what makes prose work but can’t produce prose that works the same way. The Purple Thread—discount thread the color of grief, the color of a dead brother’s septic skin, stitched into a wound by a girl who notices the coincidence without understanding its weight—emerged because the author lived in that character’s consciousness. Every AI system that attempted the same scene produced symbolism that was constructed for effect rather than discovered through inhabiting a life. The paper’s framework explains the mechanism: embodied reasoning requires grounded experience, and these systems don’t have it. The failures aren’t bugs. They’re architecture.

The paper gives us the taxonomy. What it doesn’t quite give us—what my experiments were reaching toward—is the recognition that creative writing sits at the intersection of every failure category simultaneously. A novel requires informal reasoning (understanding subtext, irony, unreliable narration), formal reasoning (maintaining plot logic and continuity across hundreds of pages), and embodied reasoning (spatial coherence, physical action, experiential authenticity). The failures don’t just add up. They compound. Each category of limitation interacts with every other, producing the specific kind of sophisticated-sounding wrongness that makes AI editorial feedback so dangerous: confident, articulate, and disconnected from what the text is actually doing.

The failures aren’t limited to creative evaluation either. A randomized controlled trial published this week in Nature Medicine tested whether AI chatbots could help over 1,200 participants navigate medical scenarios—symptoms, history, lifestyle details—and determine the right course of action. Participants using chatbots identified the correct diagnosis about 34 percent of the time. They were no better than the control group, who just Googled it.

When researchers entered the full medical scenarios directly into the models, accuracy jumped to 94 percent. The same bounded-versus-unbounded pattern: give the system clean, complete input and it performs. Ask real humans to describe messy, incomplete, subjective experience and the architecture collapses. Users didn’t know which symptoms were clinically relevant—the same way AI editorial systems don’t know which craft elements are structurally load-bearing—and the models didn’t compensate by asking.

The robustness failures were worse. Two participants given identical starting information—severe headache, neck stiffness, light sensitivity—described the problem slightly differently. One got told to rest in a dark room and take over-the-counter pain relief. The other was told to go to the emergency room immediately. The underlying condition was the same. The phrasing changed; the triage flipped. That’s the medical version of the same framing sensitivity that produced three different wrong developmental edits from three different models evaluating the same manuscript—except here the cost isn’t a bad revision note. It’s a missed subarachnoid hemorrhage.

This matters beyond craft arguments because the writing community has spent the last year making decisions based on a fundamental misunderstanding of what these systems can and can’t do.

SFWA wrote emergency policy banning AI from the Nebula Awards—panic-driven rules that can’t be defined and can’t be enforced, protecting against a threat that doesn’t exist. No AI system is going to produce Nebula-caliber fiction, because the architectural limitations the paper just catalogued are the same ones that prevent these systems from generating authentic voice, emergent symbolism, or consciousness filtered through lived experience. The award was never in danger. But SFWA wrote policy anyway, driven by members who called LLM output “assembled stolen work”—a description that doesn’t remotely correspond to how the technology actually functions. The real limitations run far deeper than copyright concerns.

Meanwhile, publishers are deploying AI to screen manuscripts—using systems the paper just demonstrated can’t reason about context, intent, craft, or the difference between depicting injustice and endorsing it. AI “sensitivity readers” flag my characters for “problematic misgendering” when a woman successfully disguised as a boy is called “lad.” They flag social commentary as the thing being commented on. Without specific prompting telling them what craft elements to look for they can’t detect irony, can’t recognize satire, can’t distinguish between a character being problematic as a literary critique and an author endorsing the content.

Even worse, genuinely harmful stereotypes will pass with a green light while a damning literary indictment of child sex trafficking is falsely labeled as CSAM.

That’s not just a minor pattern matching error; it’s the kind of thing that can destroy careers.

These are application-specific failures in the paper’s taxonomy—systems that look functional in narrow benchmarks but collapse when deployed in domains requiring the kind of reasoning the architecture can’t support.

The irony is that while the community continues to argue about whether AI will replace authors, the actual threat to indie writers goes completely unaddressed. Content mills posing as “prolific” indie authors with six-figure advertising budgets are already suffocating independent voices—flooding discovery channels and outspending real authors on ads while paying ghostwriters poverty wages to maintain production volume. AI will just let them do it cheaper. I know, because I verified it in a blind test: a bestselling indie author’s operation couldn’t distinguish AI-generated prose from professional craft and actively preferred the AI output because it matched what their business model had optimized for: competent plot beats executed competently, completely stripped of anything and everything that makes great fiction great. I.e. genre slop.

Pattern-matching succeeds when the bar is set at pattern-matching height. It fails—fundamentally, architecturally, predictably—when the task requires reasoning these systems can’t perform.

The paper’s taxonomy makes this distinction rigorous rather than rhetorical.

I’m not taking a victory lap, although I’ve earned it. The evidence was always there—in my experiments, in the research I cited from MIT and Harvard and Cornell and University College Cork and the PMC empathy studies, in Ted Chiang’s “blurry JPEG” framing, in the Booker Prize’s assessment that training on Mozart produces Salieri at best.

What the paper adds is structure. A taxonomy that organizes fragmented findings into a coherent framework and makes the patterns impossible to dismiss as anecdotal. Whether the writing community reads it is another question. They’re still arguing about Nebulas while content mills buy the shelf space out from under them.

Discover more from The Annex

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.