The world’s most famous survival story might just be the worst portrayal of human nature ever.

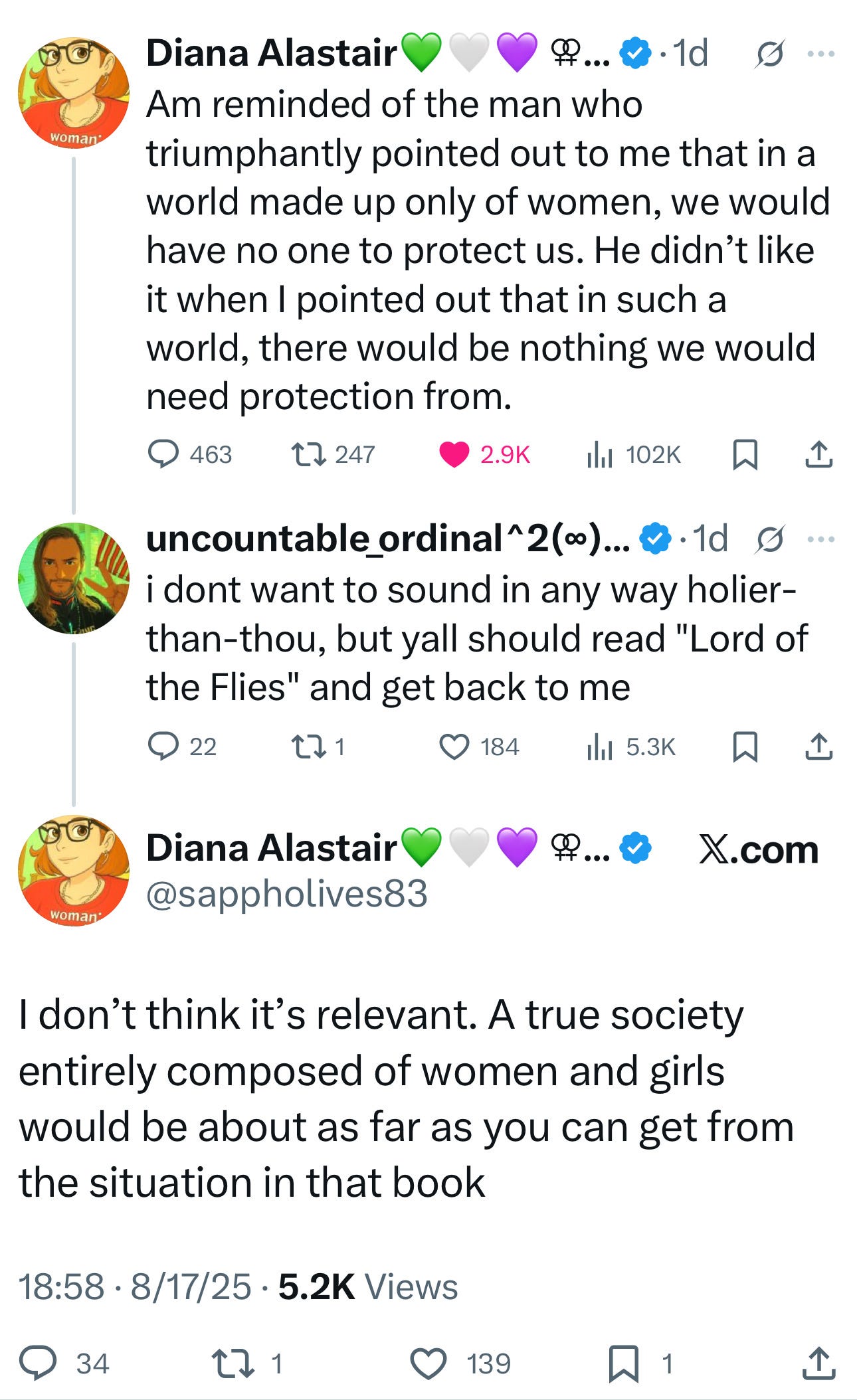

While imbibing copious amounts of coffee and trying to jumpstart my ADHD brain this morning, I came across an interesting exchange on Twitter:

It sent me down a rabbit hole, because it reminded me of something I’d read about a few years ago—a real-world “Lord of the Flies” scenario that happened in 1965. Six boys actually did get stranded on a deserted island for over a year. But instead of descending into Golding’s nightmare of tribal warfare and murder, they thrived through cooperation and friendship.

The Twitter debate touches on something deeper than just gender dynamics—it’s about a fundamental assumption we’ve all internalized about human nature. The Lord of the Flies has become our cultural touchstone for what happens when the “thin veneer of civilization” gets stripped away. Golding, shaped by his World War II experiences, crafted a deliberately dark allegory where British schoolboys start with good intentions—electing Ralph as leader, establishing rules, maintaining a signal fire—but fear of an imaginary “beast” fractures their society. Jack exploits that fear to seize power, and what follows is brutal: ritualistic hunting, face paint, tribal chanting, and eventually murder.

The message hits hard: strip away adult supervision and social rules, and children become monsters. It’s a compelling vision that’s shaped how we think about human nature for decades. But here’s what’s interesting about that Twitter exchange—even Diana’s sharp response about women being different still accepts Golding’s basic premise that someone will inevitably devolve into savagery without civilization. She’s just arguing it would be men, not women.

But what if that entire premise is wrong?

In 1965, six teenage Tongan boys proved it might be. Bored with their Catholic boarding school, they “borrowed” a fishing boat to sail to Fiji. A storm wrecked their boat and left them stranded on ‘Ata, a completely uninhabited volcanic island in the Pacific. These weren’t random classmates thrown together by disaster—they were friends who’d planned an adventure together.

What they did next challenges everything Golding taught us to expect. Instead of panic or power struggles, they immediately organized. They split into two teams of three, rotating daily between work and rest—sophisticated resource management that prevented burnout and ensured critical tasks got done. They maintained a signal fire (successfully, unlike Ralph’s crew), built solid shelters, created a garden, and established a fresh water system. When Stephen fell off a cliff and broke his leg, the others set his bone with sticks and leaves, nursed him back to health, and adapted their work system to include him.

When arguments broke out—because teenagers will be teenagers—they had a system. Disputants would go to opposite ends of the island until they cooled off and could work things out rationally. No violence, no power grabs, just practical conflict resolution. They even organized recreation—music, games, just hanging out. They understood that staying sane was as important as staying alive.

Having served in the military, I’ve seen cooperation work brilliantly under pressure, but it required rigid hierarchy, clear command structure, and discipline drilled into everyone. The Tongan boys pulled off something arguably harder: cooperation without any formal framework imposed from above. Yet they still naturally organized themselves into functional roles and systems. This suggests something important—maybe military hierarchy isn’t imposed against human nature, but actually reflects how we naturally organize when facing challenges. We don’t need civilization to impose order on our chaotic nature. We ARE civilization. We create order because that’s what we do.

When Australian sea captain Peter Warner found them fifteen months later, they were healthy, organized, and still friends. They’d succeeded where Golding’s fictional boys had failed spectacularly.

The research backs this up. Forget Golding’s “humans are selfish” narrative—science says otherwise. Sarah Hrdy has shown that kids are wired to share, not hoard. Our species succeeded through what she calls “cooperative breeding”—basically, raising kids as a team sport. Christopher Boehm’s work shows our ancestors thrived by sharing the load, not by crowning the loudest jerk. Even Michael Tomasello’s studies of very young children prove toddlers will split their snacks without a tantrum. The Tongan boys weren’t outliers; they were just doing what humans do when fear doesn’t call the shots.

And the Tongan boys aren’t unique. On 9/11, strangers helped each other evacuate, opened their homes, and organized spontaneous boat rescues. The London Blitz saw communities come together under bombing rather than falling apart. After Japan’s 2011 tsunami, the world watched orderly mutual aid emerge from catastrophe. In 1972, a Uruguayan rugby team survived 72 days in the Andes, maintaining group cohesion and shared decision-making despite facing starvation, freezing temperatures, and watching friends die.

Yes, there are counter-examples. Rwanda, Bosnia, and other horrific breakdowns show humans are capable of terrible things. But maybe the question isn’t whether we’re inherently good or evil—maybe it’s about understanding the conditions that promote cooperation versus conflict.

The gender research Diana cited is real and important. Deborah Tannen’s work shows that women and girls do tend to prioritize relationship maintenance over hierarchy establishment in conflict situations. Alice Eagly’s research finds that women more often use collaborative, consensus-building approaches while men default to competitive, dominance-based strategies. But the Tongan boys’ story suggests that even teenage boys—exactly the demographic both Golding and Diana assume would descend into tribal warfare—can choose cooperation when the conditions are right.

Those conditions matter. The Tongan boys were already friends with pre-existing bonds and trust, unlike Golding’s random assortment of schoolboys who might have had rivalries before they ever hit the island. They had practical skills from growing up in Tonga—fishing, construction, working with tropical environments. They’d been raised with cultural values emphasizing community cooperation. And crucially, they made good early decisions about shared leadership and conflict resolution that created positive feedback loops.

But here’s what strikes me most: their story was basically unknown until historian Rutger Bregman highlighted it in his 2020 book Humankind. A real story of cooperation and resilience remained invisible while Golding’s fictional story of violence and chaos became cultural gospel. We’ve internalized the idea that without adult supervision, children—especially boys—will turn savage.

Both stories reveal something true about human potential. Golding’s fiction captures real human capacities: our susceptibility to fear and manipulation, our potential for violence, the fragility of social order. The Tongan boys’ experience reveals other truths: our capacity for cooperation, our ability to create order from chaos, the strength that comes from shared purpose and mutual trust.

In our current world, dealing with everything from climate change to social polarization, we need both stories. We need Golding’s caution about what we could become, and the Tongan boys’ example of what we can be. The real question isn’t whether human nature is fundamentally good or evil—it’s what kind of humans we’re raising, and what tools we’re giving them for the challenges ahead. Are we teaching them to fear each other, or to work together? Are we preparing them to compete or cooperate? The answer might determine which story—Golding’s or the Tongan boys’—becomes our reality.

Ryan Williamson is a former U.S. Army Cavalry Scout who writes speculative fiction like the Doomsday Recon trilogy and the upcoming Dark Dominion sequence, wrestling with what makes us heroes or monsters. When he’s not crafting worlds or digging up real-life stories of grit for inspiration, he chases five-star reviews, motorcycles, and other dopamine hits.

Discover more from The Annex

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.