Someone will look at the video embedded below and dismiss it as slop. AI-generated. Just a prompt. No skill, no creativity, no legitimate artistic labor. They’ll scroll past without watching, confident they already know what it is.

Someone else will look at it and think I clicked a button. They’ve seen the marketing: describe what you want, get a video. They’ve seen the viral posts claiming whole movies made in an afternoon. They’ll assume this took minutes.

Both are wrong in ways that erase me.

I’m a novelist without a film budget. I want to make book trailers, music videos, action sequences—things that require actors and cameras and sets I don’t have and can’t afford. AI video tools let me make things I couldn’t make otherwise. The technology isn’t at commercial production quality yet, but it’s good enough to explore, to learn the craft, to tell stories in a medium I’ve been locked out of.

What follows is a production breakdown for ninety seconds of narrative video. I decided to write this article because both lies—the dismissal and the overclaim—depend on not knowing what the work actually looks like.

It started with six seconds of confident incompetence.

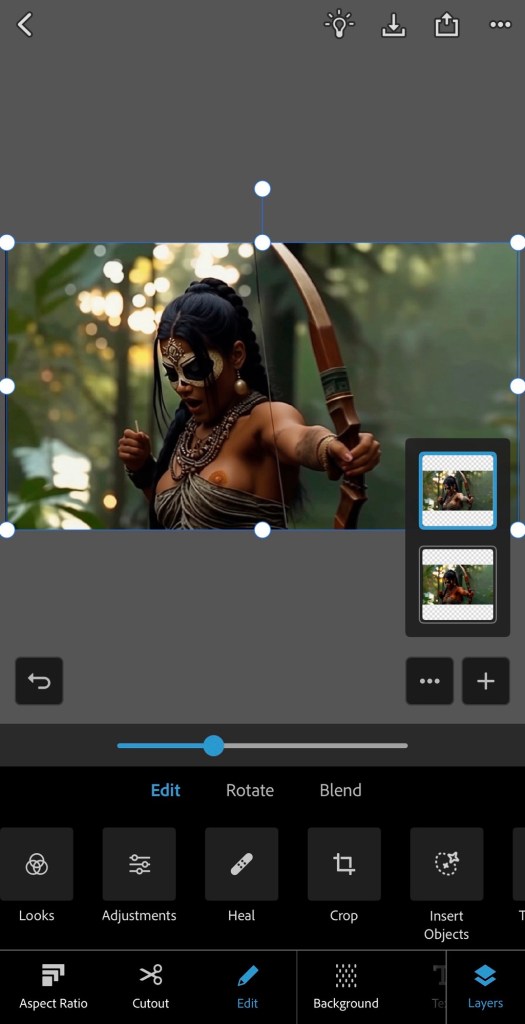

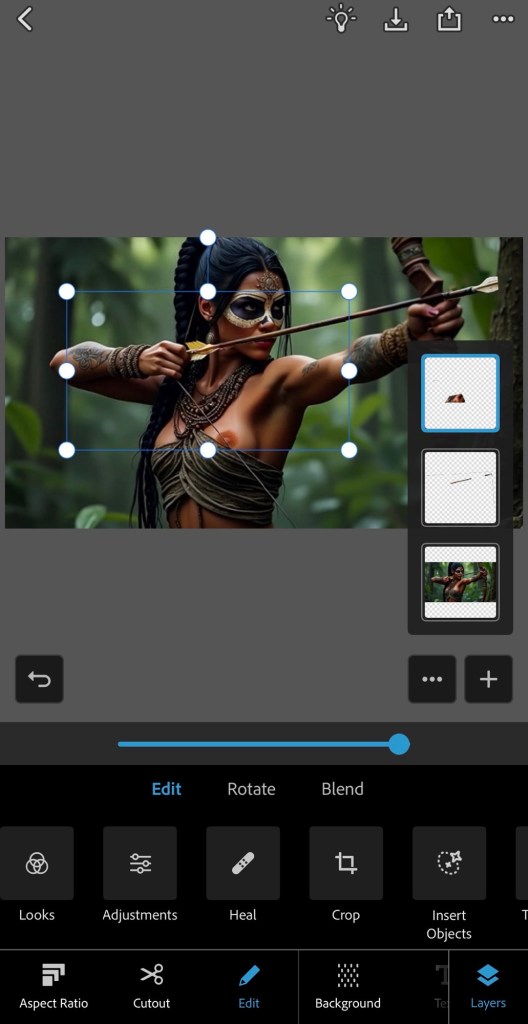

Grok generated this. The bow flexes backward when drawn. The fletching is on the arrowhead and the end of the arrow shaft. And—this is where a female friend weighed in—given the attire and the mechanics of drawing a bow, there should be nipple peek. The system generated a pose and costume that create predictable physical consequences, then generated impossible fabric behavior. Probably because it has no training data for fabric displacement during bow draw; maybe because moderation blocked it. Who knows. But the AI obviously doesn’t understand that drawing a bow lifts and compresses tissue in ways that interact with what you’re wearing. It just generates what looks plausible without reasoning about why.

I wanted to do it properly. Bow flex in the right direction. Anatomically correct fletching. And the wardrobe malfunction my friend insisted physical reality dictated because it’d make her chuckle.

That was supposed to be the whole project. A corrected six-second gag to share with a friend.

Then I decided I wanted an intro. Start high in the trees, pan down to a small figure walking through the jungle. Follow her stalking through the woods, setting up to take the shot. And once I had an intro, I obviously needed an ending. Make it a blooper reel. The actress goes off script—“Oops! That was awkward. Can we even use that take? Can you airbrush out the nipple or something?” Director’s voice from behind the camera: “Sure thing, Kozticquiahuih. We’ll fix it in post.” Clapboard snaps, camera pans up into the trees. End scene.

Scope creep happens when you’re actually doing the work. That’s how creativity works.

So what does ninety seconds of continuous-take narrative video actually require?

First, over seventy clips generated, each between two and twelve seconds long. Twenty-nine made the final cut. Roughly a 40% success rate, which means most of what I generated was unusable—wrong movement, artifacts, degraded frames, the AI deciding to do something bizarre with her face or hands or cocking up the bow. A hundred twenty-five keyframes created across the production. Couple dozen manual color corrections to keep her skin tone from sliding down the Fitzpatrick scale, because the animation model progressively lightens dark skin with each generation. About a hundred dollars in generation costs across multiple platforms. Two full days of labor from someone with decades of professional experience in digital art and multimedia production.

That’s the cost of ninety seconds. Roughly a dollar per second of final output, except the 40% success rate means you’re actually paying for two and a half seconds of generation to get one second of usable footage. And that’s before you account for the labor.

The entire production ran on my iPhone. Flux for the source image. Grok for the initial failure that inspired the project. Seedance for most of the animation. Kling for the clips Seedance couldn’t handle—except Kling’s content moderation rejected most of my generations, including shots with no nipple at all. The attire apparently triggered something. “Native woman in revealing costume” pattern-matches to rejection regardless of what’s actually in the frame? Would it be okay if she were white? Dunno. More research is required. So I used inferior tools because the better tool’s moderation made it unusable.

Qwen for pose adjustments and skin tone correction on keyframes—though it overcorrects super dark, so I’d end up with frames too light from Seedance and too dark from Qwen, requiring a third pass in Photoshop Express to blend them to correct skin tone. That happened a couple dozen times across the production.

I also utilized PS Express for artifact cleanup and to create the wardrobe malfunction itself, since no AI system can parse “as she draws the bow her breast lifts, exposing a nipple.” I manually edited three keyframes showing the progression, then fed them as visual prompts back into Seedance. The AI interpolated the motion between my control points.

The system does motion interpolation. I do all the actual reasoning.

Google Veo for the dialogue and lip sync. ElevenLabs for the director’s voiceover. VN Video Editor for final assembly, audio mixing, ambient jungle sounds, Aztec music, bowstring twang, clapboard marker.

The biggest problem no one mentions when they talk about AI video is you can only generate two to twelve seconds at a time. That’s it. There’s no “make me a ninety-second video.” There’s no continuity between generations. Each clip exists in isolation, with no relationship to what came before or after except what you impose on it.

I made a ninety-second short film that looks like one continuous take. No visible cuts. Camera moves fluidly from the canopy down to the jungle floor, follows her through the trees, pans, orbits, tracks, holds on the draw, catches the malfunction, stays with her reaction, pans up to end. One unbroken shot from twenty-nine independently generated clips stitched together. Each one between two and twelve seconds. Each one generated with no knowledge of the others. The only things connecting them are the text prompts I wrote and the frames I fed in.

The workflow breaks down to generate a clip, extract the final frame, correct the skin tone because it’s drifted lighter, use that corrected frame as the first frame of the next generation, write a prompt that continues the motion, generate, extract, correct, repeat. Dozens of times with a 40% success rate, meaning I generated roughly seventy clips to get twenty-nine that worked. And “worked” doesn’t mean “perfect”—it means “usable after I clean up the artifacts and fix the color.” And I didn’t fix everything. There are tons of continuity errors with the damn bow, her outfit, tattoos, earrings—infinite little details I could’ve spent days tweaking and polishing to get closer to “perfect.”

Also the playback speed is wildly inconsistent between generations. One clip renders at a natural pace, the next comes out too fast, most are slow motion. In the editor you’re speeding up and slowing down individual clips to make them feel like they belong to the same shot. Tedious work, adjusting by fractions of a percent until the motion flows. Setting speed curves so Clip B matches the end of Clip A and the beginning of Clip C.

AI doesn’t understand directions either, like left or right. You want a continuous clockwise orbit around a character that spans two or three clips? You’re betting 50/50 each generation whether the camera will keep moving the way it was or suddenly reverse. “Continue orbiting clockwise” means nothing to the model. It generates what looks plausible, and half the time plausible apparently means the opposite of what you needed. More waste. More regeneration.

The transitions are where it falls apart if you’re not careful. Seedance doesn’t generate clean final frames consistently. Sometimes the last several frames are blurred or corrupted, which means you can’t use them as input for the next clip. You throw it away and regenerate. Sometimes the motion doesn’t match—the ending pose of one clip doesn’t flow into the starting pose of the next. More regeneration. More often the lighting shifts between clips in ways that make the cut visible even when the motion matches. Color correction, or more regeneration, or you just live with it because life is short.

Making twenty-nine separate clips look like one continuous shot isn’t a technical feature of the tools. It’s labor. It’s understanding how motion flows, where the eye will catch a seam, how to time generations so the ending of one feels like the beginning of another. It’s solving problems the tools create rather than problems the tools solve.

The source image came from Flux. Decent quality, good reference for character consistency across a hundred twenty-five keyframes and seventy clip generations.

Unfortunately I didn’t notice until after I was deep into the project that she was missing her left pinky finger.

Fixing it would have required regenerating thirty-nine seconds of content—twenty-plus new clips, fifty-plus new keyframes, another round of color corrections. Several hours if not another day of additional work.

So I decided the actress lost her left pinky in a tragic boating accident and we moved on.

Early-stage mistakes cascade through the entire workflow. The source image isn’t one image. It’s the template for hundreds of derivative works. Mistakes propagate.

Lessons were learned.

The wardrobe malfunction matters for the argument I’m making, so let’s chat about what it required.

AI systems can’t model causal physics. They don’t understand that drawing a bow involves shoulder rotation, pectoral engagement, tissue displacement, and fabric interaction. They generate poses that look like archery without reasoning about what archery does to a body wearing that outfit. My friend was right: the physics dictate the outcome. The AI’s version was impossible.

So I did the physics reasoning myself. I edited keyframes showing the progression—initial hint of the areola as she raises the bow, full exposure in all its glory at draw, then her noticing what happened. Fed those back into the animation tool. Let the AI interpolate between my physics-informed control points.

That’s the division of labor the marketing doesn’t mention. You reason about causality, anatomy, physics, fabric behavior. The AI generates motion between the frames you’ve defined. At a 40% success rate. With systematic skin tone drift requiring manual correction. With artifacts you have to clean up by hand. With content moderation that blocks better tools for opaque reasons.

There’s a version of this piece that’s just documentation. Tool by tool, problem by problem, solution by solution. I have that information. You could replicate my workflow from it. Maybe I’ll write a tutorial someday.

But today is not that day and that’s not why I’m writing this.

I’m writing this because I’m sick of both lies. The people who dismiss AI video as slop, no skill required, not legitimate creative work—the production breakdown proves them wrong. And the people who claim they made a movie by clicking a button—they’re lying in ways that validate the dismissers. They make it sound easy, which makes the dismissal sound reasonable. If it’s really just prompts, then yeah, it’s slop.

But it’s not just prompts and there’s no button. It’s writing, direction, storyboarding, correction, curation, physics reasoning, color work, artifact cleanup, narrative structure, audio design, and enough professional expertise across enough disciplines to solve problems when the tools fail.

Which they do, at least 60% of the time.

The technology isn’t ready for commercial production. The artifacts are too frequent, the consistency too fragile, the success rate too low. I wouldn’t use this workflow for a client deliverable.

Someday I think it will be, and when it is I’ll be ready.

But it’s good enough right now to explore. Good enough to learn. Good enough to make book trailers and music videos and action sequences that I couldn’t make otherwise. Good enough to tell stories in a medium I’ve been locked out of by the cost of actors and cameras and sets. Good enough to express myself creatively in ways I couldn’t otherwise.

I wish I were a filmmaker with a studio budget. I’m not. I’m a novelist who wants to make things he can’t afford to make the traditional way. These tools—imperfect, inconsistent, requiring constant correction—let me do that.

That’s not slop. It’s not “writing a prompt.” And it sure as hell isn’t just “clicking a button.”

Anyway, here’s the final short film. Enjoy.

Tools used

- Flux 1.1 (web interface) — Source image generation

- Grok (X mobile app) — Initial animation test

- Seedance 1.0 Pro (Freepik mobile app) — Primary animation

- Kling O1 (Freepik mobile app) — Secondary animation

- Qwen Image Edit Plus (Mage Space mobile website) — Keyframe editing, pose adjustments

- PS Express (mobile app) — Color correction, artifact cleanup, manual edits

- Google Veo 3.1 (Freepik mobile app) — Dialogue and lip sync

- ElevenLabs (mobile app) — Voiceover

- VN Video Editor (mobile app) — Final assembly, audio mixing

100% of production including pre and post was done on iPhone 14 Max.

Discover more from The Annex

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I’m glad to see see Kozticquiahuih is getting work. Such a beautiful and poetic name.

There’s no need to repent at all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hehe

LikeLike

There’s not even a need to go to confession merely for knowing a name.

LikeLike