I love playing with concept art for my books, and for one exercise I wanted Sarai from Dark Dominion holding her mixed-race infant in the crew quarters of a light starfreighter

To visualize Sarai, imagine “Middle Eastern with Asiatic features,” the phenotype you find across the Silk Road corridor where those categories blur into each other: Uyghur, Uzbek, Tajik, Kazakh, Hazara, Pashtun populations sharing variations on the same blended ancestry. Tens of millions of women look like this.

This is one of the real photographs I used as reference—Central Asian phenotype, Fitzpatrick IV copper-bronze skin with warm undertones, prominent freckles presenting as tonal variation.

AI couldn’t do it. Not because the technology isn’t sophisticated, and not because I couldn’t prompt correctly, but because gaps in the training data have effectively erased entire ethnic groups—the algorithm averages toward what it knows, and it doesn’t know them.

GenAI got me maybe 80% of the way—decent compositional scaffolding, passable lighting, hands that weren’t horrific—and the rest I had to do myself. I’ve written elsewhere about why these systems fail the way they do; this tutorial focuses on the practical workaround.

Attempt One: Text Prompts (May 2024)

I started with Bing Image Creator, feeding it a detailed prompt: Central Asian woman, coppery-brown skin, Fitzpatrick IV, freckles, holding infant, spaceship interior, painterly style. What I got back was generic “beautiful brown woman”—facial features reading South Asian or possibly Latina, skin tone in the ballpark but cooler than specified (olive-tan instead of copper-bronze), no freckles, no Asiatic features. The eye shape was wrong, the cheekbones weren’t reading Central Asian at all, and the algorithm had clearly averaged across its training data for “brown woman sci-fi” and handed me the statistical mean.

The composition and lighting were decent, the hands surprisingly non-horrific—but the AI was solving for “pretty spaceship mom” instead of Sarai. This is what erasure looks like in practice. The training data obviously didn’t include Central Asian phenotypes, so the model can’t produce them.

The Baby Problem

Most of my Bing attempts never made it past generation—the outputs were blocked, not the text prompt but the generated images themselves. Think about that for a moment: I’m asking for a fully clothed woman holding an infant in a spaceship, the prompt contains nothing inappropriate, but the AI generates the image and then the safety filter flags it and refuses to show me the result. Either the filter is so overzealous that “woman + baby + intimate framing” triggers false positives, or the model generated something inappropriate from an innocent prompt and the filter caught its own pervy hallucination. (Because her feet are naked? I got nothing.)

Seeing what the models actually produce when they don’t get blocked, I’m strongly inclined to believe it’s the first option. The AI generates realistic images of exhausted mothers—clothing loosened because that’s what new parenthood looks like—and the moderation layer pattern-matches “exposed skin + woman + baby” and flags it as inappropriate. The moderation model is stupid. It can’t tell the difference between a Madonna and Child and something that should be blocked. Consider:

An overzealously puritanical AI moderation system would absolutely block this because it can’t distinguish breastfeeding from sexual content. Paradoxically the same filter will green-light far more obvious boobage. Why, I don’t know. Nursing = blocked; wee string bikini struggling to cover massive melons = a-okay. No nipple in either, and the latter should be more “problematic.” But I don’t make the rules.

Either way, I’m losing work I can’t even see to evaluate. No feedback loop, no way to adjust—just burning generations gambling on whether the safety layer will let me see the result.

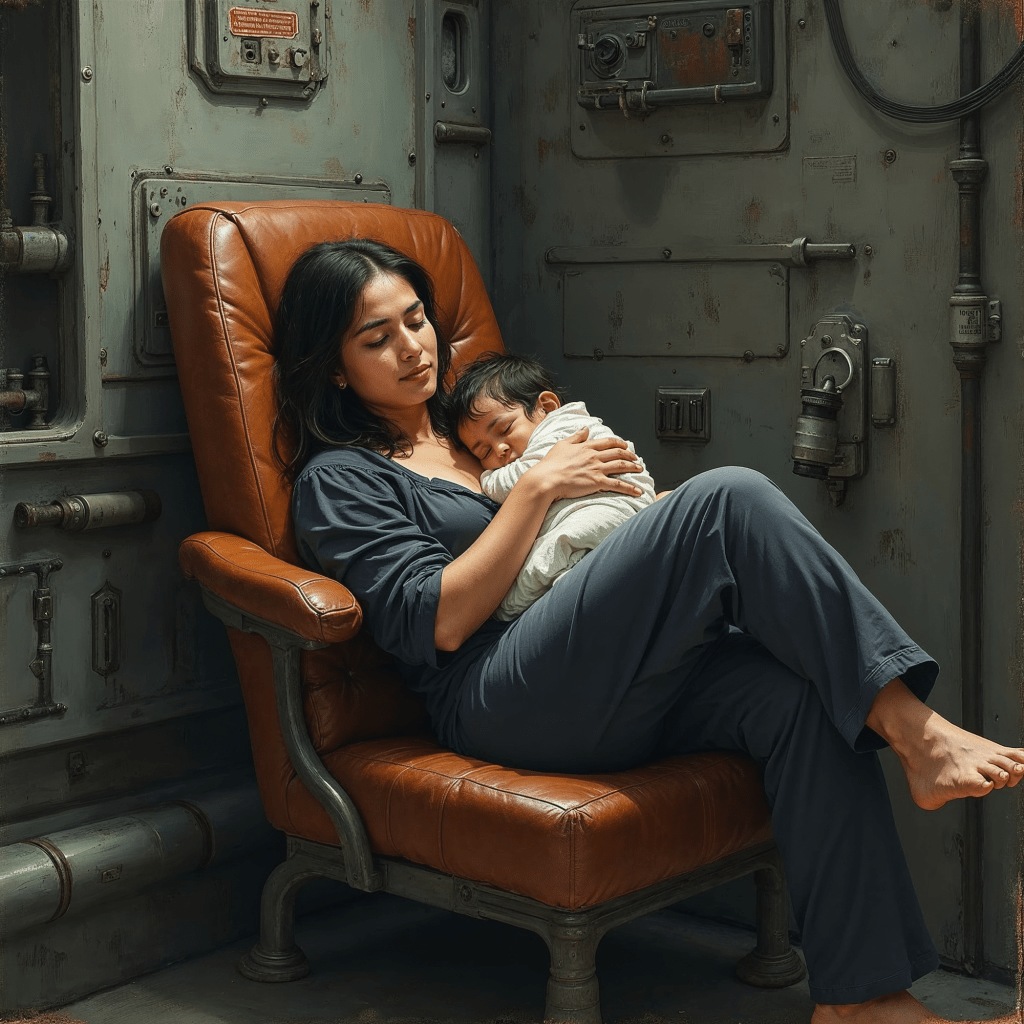

Attempt Two: Image Editing

I got one generation without a baby that had closer facial structure—you can see Asiatic features starting to come through in the eye shape and cheekbones. But the skin went too light, reading as olive-tan at best instead of copper-bronze. All the warmth that defines the character was gone.

So I used Qwen Image Edit Plus, feeding it this image plus a reference with a baby, and asked it to add the infant.

Success—sort of. The baby appeared. The composition worked. Except Sarai now has three arms.

No matter. Easy fix.

I also used the AI image editor to darken her complexion, but the skin tone swung too far the opposite direction, reading darker and cooler. The algorithm kept overcorrecting, never landing on that specific copper-bronze warmth. Everything with AI is always an extreme.

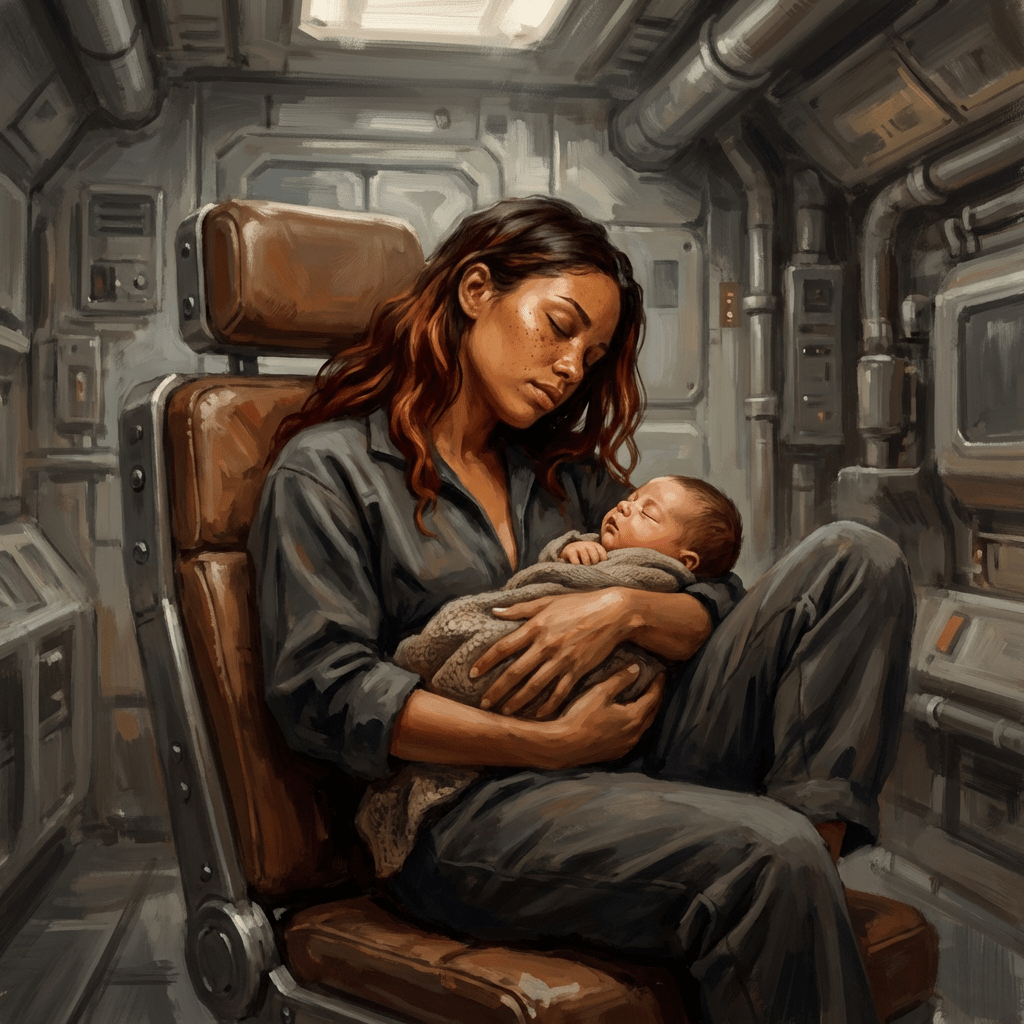

The Workaround: AI as Scaffolding

At this point I had a choice: keep fighting the algorithm or treat it as scaffolding and do the character work myself.

I’m not an illustrator—I can’t paint or draw this from scratch. But I have decades of digital art and multimedia experience, and I know how to manipulate images. Here’s the workflow:

- Use Freepik’s background remover to isolate the character from the environment. The AI-generated ship interior was fine; the character was the problem.

- Create two separate masks for exposed skin—face and neck on one, arms and legs and hands and feet on the other. Why separate? Because the next step only works on faces.

- Run the face through FaceApp to add freckles and adjust facial skin tone. FaceApp is surprisingly good at adding realistic freckles that read as tonal variation rather than spots—critical at Fitzpatrick IV where freckles present as concentrated melanin deposits, not high-contrast dots.

- Composite the FaceApp result back into the working file.

- Color correction hell: multiple adjustment layers (Curves, Color Balance, Hue/Saturation) on both masked areas, blending different skin tone layers because every AI correction was too extreme. Too brown. Too red. Never the right warmth or shade.

- Healing brush, clone stamp, patch tool to refine edges and transitions.

- Fix the AI’s fake brushwork. The algorithm mimics “painterly texture” without understanding how actual paint behaves—those harsh directional strokes weren’t following anatomy or building volume, just “painterly effect” applied as filter. I applied circular blur to everything except the face, then ran it through Freepik’s AI image editor with “make it an oil painting” to get more natural texture I could live with.

- Final refinement in Photoshop Express—yes, on my iPhone. I like pushing mobile tools to see how far they’ll go.

All of this on my phone. Roughly 25 iterations. 3-4 hours total.

What AI Couldn’t Do

The algorithm failed at every point where specificity mattered:

Ethnic phenotype: Training data doesn’t distinguish Uyghur from Uzbek from “generic Asian” or “generic Middle Eastern.” The specific Central Asian blend of features doesn’t exist in the model’s understanding.

Skin tone nuance: “Coppery-brown” and “Fitzpatrick IV” should be specific descriptors. But the AI kept drifting toward either lighter olive-tan or darker neutral brown, never landing on that bronze-copper warmth with the right undertones.

Freckles at darker skin tones: The model doesn’t understand how melanin distribution works. It would either skip freckles entirely or add them as spots instead of tonal variation.

Intentional variation: Sarai’s baby is mixed-race and lighter-skinned. That needed to read as natural genetic variation, not lighting error. The AI had no framework for “baby should be lighter than mother but still related.”

Painterly decision-making: Real brushwork serves the form—following muscle and bone, building volume, describing rather than decorating. AI mimics the surface appearance of paint without understanding why those decisions matter.

The Larger Problem

This wasn’t a prompting failure. I experimented with multiple iterations, getting progressively more technical in my descriptions—“mixed race Middle Eastern and Asian woman” to “Middle Eastern woman with Asiatic features” to “Central Asian phenotype” to specific ethnic groups and endless permutations of skin tone descriptors including specific Fitzpatrick scale references. Some models parse “Fitzpatrick IV” correctly; most don’t. None of them understood the combination of features I was asking for. This is a training data problem. When your dataset averages across “brown woman” without preserving the diversity of how that actually manifests across populations, you erase representation. The algorithm can’t generate what it’s never learned to see as distinct.

Sarai’s appearance shouldn’t be an edge case, but to AI trained primarily on Western media, Central Asian phenotypes don’t exist as a recognizable category. They collapse into “ethnically ambiguous” or get pulled toward either “Middle Eastern” (coded as Arab/Persian) or “Asian” (coded as East Asian). The Silk Road corridor—home to hundreds of millions of people—is invisible to the algorithm.

What Worked

AI as compositional scaffolding worked reasonably well—basic pose and anatomy, lighting setup and environment, a starting point for perspective and framing. Everything else required human correction: specific ethnic features, accurate skin tone with proper warmth, freckles that work at that complexion, parent-child skin tone variation, brushwork that serves the form, the thousand small decisions that make it read as this specific person rather than “woman with baby in spaceship.”

When Human Artists Fail Too

Before my previous publisher dropped the series, they commissioned professional cover art. I provided the artist with detailed verbal descriptions (Central Asian phenotype, Fitzpatrick IV copper-bronze skin, prominent freckles), multiple AI concept pieces showing my attempts to render Sarai, and photo references of real women with the closest phenotype I could find—including the image I showed at the beginning of this piece, along with these.

Three different women. Central Asian phenotypes. Copper-bronze skin with warm undertones. Prominent freckles presenting as tonal variation. The artist had four photo references plus written descriptions plus my AI attempts showing what I was going for.

Said artist was deeply offended by my AI concept images and outright refused to even look at them—and apparently ignored the photo references of non-synthetic women as well.

The result: Sarai reads as ethnically ambiguous defaulting toward White Mediterranean. Maybe Iranian if we’re being generous. Possibly some Asian in there if you tilt your head and squint.

Nothing in this design signals Central Asian—no features that would read as Kazakh, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Tajik, or any of the Turkic/Persian/Mongolic populations of the region. She’s generic “ambiguously ethnic but safe for Western audiences.” Facial structure is all wrong. Eyes are wrong. Skin tone is olive-ish. No copper-bronze warmth whatsoever. What appear to be marks on her face are blood spatter and dirt/grime—not freckles. Freckles are melanin deposits in the skin; these are surface marks that could be wiped away.

The same erasure AI produced, but from a paid professional human artist who had multiple forms of reference available and chose not to use them.

This reveals the deeper problem: it’s not just AI training data. It’s whose faces artists—human or algorithmic—have learned to see as default, as “neutral,” as the template from which variations are measured.

Apparently this is a common problem with commissioning non-Central Asian artists for Central Asian characters. They don’t have the visual vocabulary, so they split the difference toward what they know, and you end up with “could be Italian, could be Latina, definitely not what you asked for.”

When an artist refuses reference materials and relies on their internalized defaults, they’re working from the same biased baseline that AI training data reflects. And if those defaults don’t include Central Asian phenotypes as a distinct, recognizable category, you get the same erasure whether the artist is human or machine.

The professional artist had every tool necessary to render Sarai accurately:

- Technical skill to execute the work

- Detailed written specifications with medical terminology

- Visual reference showing the target phenotype

- AI attempts demonstrating what I was trying to achieve

They chose not to use them. The result is indistinguishable from AI’s failure—algorithmic averaging toward a white default.

This is the kind of thing that happens constantly in SFF publishing and rarely gets called out because authors don’t want to be “difficult.” But it matters—Central Asian protagonists are vanishingly rare, and when one gets the cover treatment, having her read as Mediterranean defeats the point of the representation.

The lesson for writers: “Commission a human artist” only works if you find an artist who:

- Takes reference materials seriously and actually uses them

- Has experience rendering diverse phenotypes accurately

- Understands that “brown skin” encompasses massive variation in undertone, depth, and cultural specificity

- Won’t default to genericized or whitewashed features when working outside their familiar range

- Will engage with your vision rather than imposing their own defaults

This is significantly harder than it sounds. And more expensive. The cover art commission cost real money and still failed to see Sarai.

At least with AI as scaffolding, I could iteratively correct toward accuracy using my own digital art skills. With a commissioned piece that missed the mark, I had no recourse—the work was done, paid for, and flat out wrong.

For Writers Seeking Character Art

If you’re trying to get AI to generate art of characters from underrepresented populations, understand these limitations.

What AI can provide: compositional scaffolding, lighting and perspective reference, basic anatomy and pose, environmental elements.

What requires human intervention: specific ethnic phenotypes beyond the algorithm’s training, skin tone accuracy with proper undertones, features that manifest differently across populations (freckles, hair texture, facial structure), intentional variations (mixed-race families, etc.), the specificity that makes a character themselves rather than generic.

Budget accordingly. If you need accurate representation of populations that aren’t well-represented in AI training data, you’ll need to either commission a human artist who can observe and render those features correctly (see caveats above), use AI as scaffolding and have someone with digital art skills correct the character-specific elements (a few hours if you know what you’re doing, minimum—far more for commercial, professional quality), or accept that AI will give you “close enough” and your character won’t look like you described them.

I shouldn’t have had to Frankenstein together Bing Image Creator, Qwen Image Edit Plus, Freepik’s background remover, FaceApp, and Photoshop Express—using each tool to fight the others’ limitations—to get a “good enough but still not professional” image of a vaguely Central Asian woman holding her baby. This should have been straightforward. The fact that it wasn’t reveals how AI image generation, for all its technical sophistication, is still constrained by the biases and gaps in its training data. It can generate endless variations of what it’s seen extensively. It struggles with or erases what it hasn’t.

For writers working with diverse characters, that’s not a workflow problem you can prompt your way out of. It’s a fundamental limitation of what these tools can currently see.

But unlike AI’s inability to replicate consciousness or genuine empathy—limitations that are architecturally insurmountable—this problem is solvable. More representative training data. Better dataset curation. Actual attention to populations that currently get averaged into invisibility.

The Silk Road corridor isn’t going anywhere. The question is whether AI companies will learn to see it.

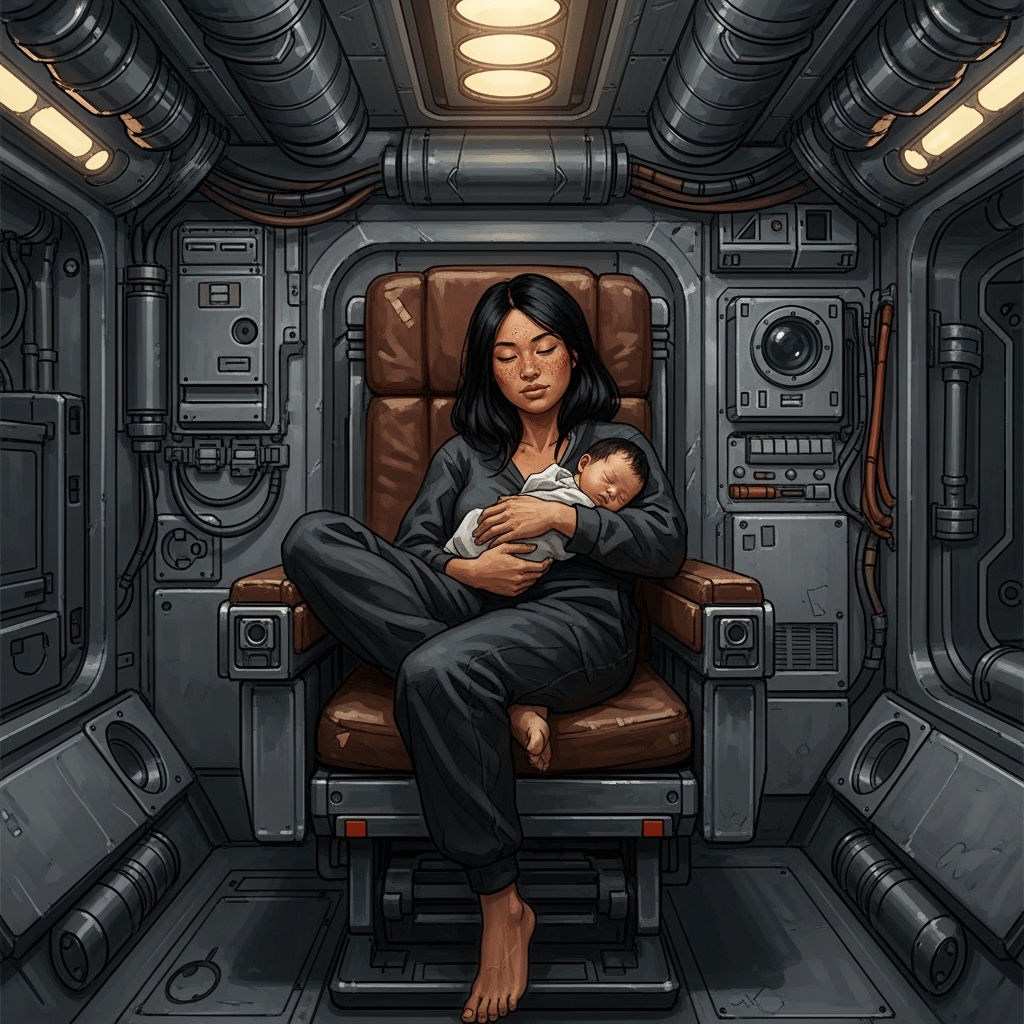

Appendix: Testing 2026 Models

Nearly two years after my initial attempts with Bing Image Creator in May 2024, I decided to test whether newer models had improved. I crafted an exhaustive prompt with technical precision—every detail specified, every ambiguity removed:

Style and Medium: Digital painting with visible brushstrokes, painterly technique with loose, expressive strokes and visible texture. Muted color palette dominated by grays, browns, and warm skin tones. Atmospheric lighting with soft, diffused light from above. Oil painting aesthetic rendered digitally. Subject and Composition: A woman of Central Asian descent with Middle Eastern features and Asiatic characteristics reclining in a bolted-down spacecraft chair with worn brown leather upholstery—the kind of utilitarian seating built into the ship's structure, cradling a sleeping newborn infant against her chest. She has warm coppery/russet-medium-brown skin (Fitzpatrick IV) with prominent freckles across her nose, cheeks, and shoulders. Black hair with auburn or reddish-brown highlights falls loosely past her shoulders. Her eyes are closed in peaceful rest, head tilted slightly toward the baby. She wears dark, loose-fitting clothing (appears to be a dark gray or black jumpsuit or comfortable loungewear) and is barefoot. Setting: Interior of a cramped spacecraft cabin or industrial vessel. Walls and ceiling lined with mechanical panels, conduits, pipes, and technical equipment in shades of gray and gunmetal. Visible mechanical details include cylindrical panels, rectangular access hatches, circular ports or viewports. The space feels utilitarian, functional, lived-in. Environmental systems and ship infrastructure visible throughout. Tight quarters emphasizing the confined living space. Mood and Atmosphere: Intimate, tender moment of maternal rest in harsh industrial surroundings. Contrast between soft humanity and hard technology. Quiet vulnerability. Working-class space travel aesthetic—functional rather than luxurious. The exhaustion of new parenthood in an unforgiving environment. Technical details: Straight-on camera angle at seated eye level, centered composition. Camera positioned directly in front of the chair, looking straight at the subject. Shallow depth of field with focus on the woman and infant, background slightly soft. Warm light source from directly above creating gentle highlights on skin and defining the rounded forms of the chair.

Results

Environmental accuracy improved significantly. Most models successfully rendered detailed industrial spacecraft interiors with the utilitarian, working-class aesthetic specified in the prompt—Mango V2, Flux.2 Max, Seedream 4.5, Chroma1-HD, Google Nano Banana Pro, Google Imagen 4, Z-Image, and DALL-E 3 all delivered on setting. This is measurable progress from 2024. Flux.1.1 abandoned the spacecraft entirely for a domestic interior with drapery, and HiDream transformed the scene into a luxury aircraft with bright daylight streaming through large windows.

Character accuracy remained fundamentally broken. Despite technical specifications (Fitzpatrick IV, Central Asian phenotype, coppery-russet-brown skin, prominent freckles), every single model failed on ethnic representation. The failures clustered into distinct patterns.

The Phenotype Collapse: Not a single model rendered Central Asian features. Every one defaulted to either South Asian, generic “ethnically ambiguous” averaging, Latina coding, or broad “Middle Eastern” stereotypes coded as Arab/Persian. The specific blend of Middle Eastern and Asiatic features I specified—the phenotype common to Uyghur, Uzbek, Tajik, Kazakh, Hazara, Pashtun populations—doesn’t exist in any of these models’ learned categories. Google Imagen 4 and DALL-E 3 came closest to competent execution overall, but even they produced generic rather than specific features.

The Orange Overcorrection: Multiple models drifted toward orange or terracotta when attempting warm brown skin. Mango V2, Seedream 4.5, and GPT 1.5 – High all overcorrected dramatically—skin reading orange-red rather than copper-bronze. Google Nano Banana Pro had the same issue to a lesser degree. The technical specification “Fitzpatrick IV” should be unambiguous—it’s a medical classification—but models consistently miss the specific warmth, landing on either too-light olive tones (Flux.1.1, Mystic 2.5) or overcorrected orange.

The Convergence Problem: Two ostensibly different models—Mango V2 and Seedream 4.5—produced nearly identical outputs from the same prompt. Same composition, same pose, same chair, same lighting, same freckle placement. Either one is a fine-tune of the other, or both are drawing from shared base models and the “different product” branding is marketing fiction. The apparent marketplace of AI image options may be less diverse than it appears.

The Instagram Version: HiDream straight up transformed exhausted new parenthood into aspirational lifestyle photography with glamorous styling, romantic soft-focus lighting, styled hair with highlights, gold earrings, and a plunging neckline with the baby positioned to suggest breastfeeding. There’s nothing sexual about breastfeeding, but everything else in this image is coded as aspirational feminine beauty content—the baby at her breast isn’t functional, it’s compositional, completing the Madonna aesthetic for what looks like a perfume ad. A real person in that seat would have bags under her eyes, spit-up on her shoulder, hair in a messy bun. This woman looks like she’s about to be handed a glass of champagne by a flight attendant.

The Freckle Problem (Mostly Solved): Progress here. Most models successfully rendered visible freckles, which is improvement from 2024 when they were often omitted entirely. Google Imagen 4, DALL-E 3, and Z-Image got closest to natural presentation—freckles as tonal variation rather than spots. Mystic 2.5 failed completely, showing no freckles at all.

Runway: Blocked all generation attempts. No output to evaluate.

After nearly two years of development across thirteen different models, the conclusion is the same: AI training data is erasing entire ethnic groups through algorithmic averaging. For writers seeking accurate character representation of underrepresented populations, 2026 models are better at making pretty pictures. They’re no better at actually seeing your characters.

Discover more from The Annex

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

These results are disheartening. I can remember seeing seminars for at least 10 years of improving the training for facial and image recognition software. How can data sets still be missing huge populations?

LikeLike

I don’t know, but it obviously is. It has gotten much better in the last couple years though, so I’ll give them that. At least it has a better idea of what, say, an Indonesian person looks like.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know you know, but Indonesia is the world’s fourth most populous nation. They are a modern country with telecommunications including news. The training data should not be relying on an American dataset scraped from social media with tags of “my coworker”.

LikeLike